Felt Presence | The Roses | The Images | The Relics | The Pilgrimage | Response to Benjamin

At various sacred sites around the globe, often associated with miraculous appearances of the Virgin Mary, rose petals are alleged to mysteriously appear and fall from the sky. These modern-day relics can then travel the world, testifying to the reality of a divine presence. Some of these roses even appear to contain images.

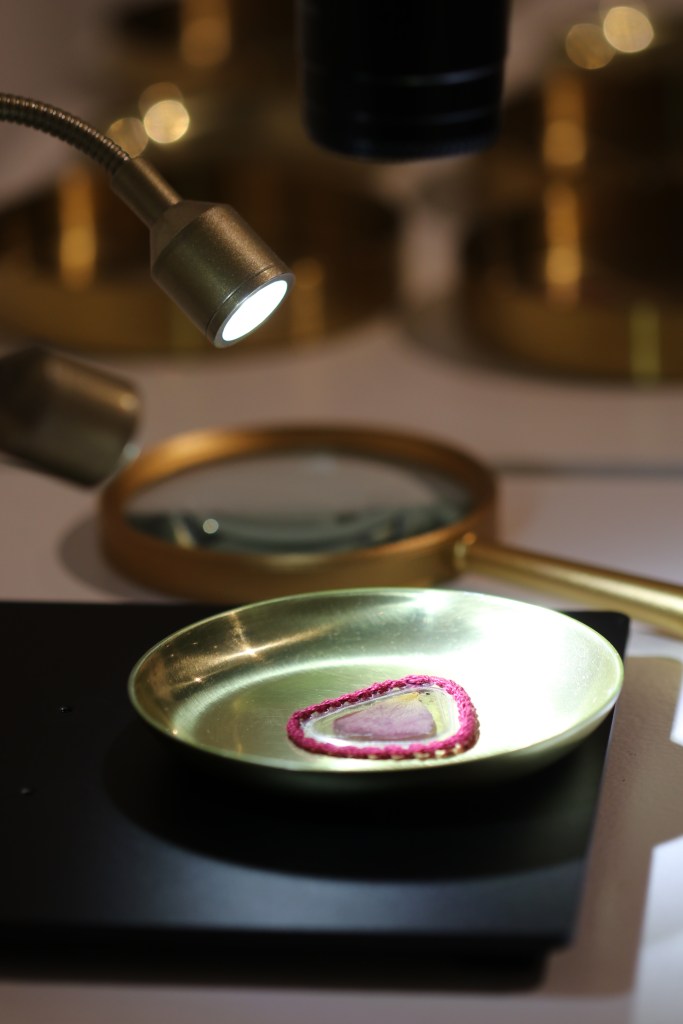

Viewers are met at the entrance of the gallery with scientific apparatuses and are encouraged to wear white cotton gloves. Rose petals placed in golden petri dishes are scrutinized to determine their origins. Are these images the result of apophenia, the innate human desire to find patterns in random data, or the communication of some unseen hand?

The digital microscope at the entrance to the exhibit sends a live feed to a large scale, rear projected rose window hanging above the exhibition. The rose petals turn into an abstracted whirlwind of light and color above the heads of those in the gallery.

What was once an individual and intimate experience at the microscope, activating the left hemisphere of the brain, becomes a communal spectacle of awe and wonder, activating the right hemisphere of the brain.

An Heirloom Relic

After my paternal grandmother passed away in 2000, and in the dividing of the estate among the family members, my father inherited an allegedly miraculous rose petal. Sandwiched between pieces of clear plastic and bound in red cord, the desiccated flower reveals an unmistakable image: a silhouette hanging on a cross. The physical object is striking to behold. The image blends into the faded surface of the petal when held in your palm, but the moment you hold it up to the light, the cross explodes forward in perspective.

My father believes that the rose petal dates to the 1930s and was originally part of a bouquet blessed by a parish priest. Multiple images allegedly appeared on these petals, and they were distributed among the congregation. One of these made its way to my Great Aunt Helen, and then to my grandmother. However, when speaking with my Aunt Diane, a different story emerged. She states that the petal was plucked by my grandmother from a rose bouquet at the funeral of a beloved friend. This person was believed to be particularly holy, and in remembrance of her, my grandmother made the plastic housing as a kind of reliquary, a container to memorialize her and to use as a bookmark in her study Bible. It was only years later that she discovered a materialized image of a cross. There were no illustrations in the Bible that the image could have transferred from.

It is not surprising that conflicting narratives exist, as these objects have changed hands multiple times, and knowledge of their origins is lost to time. What surprised me was how disparate the stories became within the one generation of siblings. Reflecting on this conundrum, I realized that these allegedly miraculous rose petals were profoundly related to questions I was beginning to ask about artificial intelligence-generated images.

Throughout the summer of 2022, it became clear how impactful AI image generators were going to be in every aspect of society. Programs such as Dall.E 2, Midjourney, and StableDiffusion dominated social media feeds with interesting and provocative artworks, all undeniably digital, but some which captured photorealistic or painterly qualities that mimicked the works of professionals. These technologies are paradigm-changing, and in confronting them, I arrived at the major question that changed the course of my graduate studies. When an AI program produces an image, what “hand” is doing the creation?

Assuming that there is some sort of non-human intelligence involved in creating these pictures, how were they made? And once these images arrive to us from beyond that nebulous veil, gifted to us by unseen hands, how do humans respond to them? What kind of stories do we tell about them? And, most importantly, how do these images and stories affect our beliefs?

Religious scholars and art historians call such images acheiropoieta, a Greek term which means “made without human hand.” Within Catholicism, some notable examples of acheiropoieta include the Shroud of Turin, which is believed to be Jesus’s burial cloth and which bears a representation of his entombed body, as well as the Our Lady of Guadalupe image, a portrait of the Virgin Mary said to have been miraculously emblazoned on a peasant’s cloak in the 1530s. These artifacts are controversial because both science and faith have weighed in to explain their origins, resulting in a tug-of-war of implicit biases negotiating how these images are understood among religious and secular people alike.

Our current media landscape is replete with social media-based information, photorealistic AI images, algorithms, and targeted influence campaigns, all creating an environment where powerbrokers can easily assert control over the unwitting masses. As with miraculous images, those who seek to narrativize pictures for disparate interests can do so very easily.

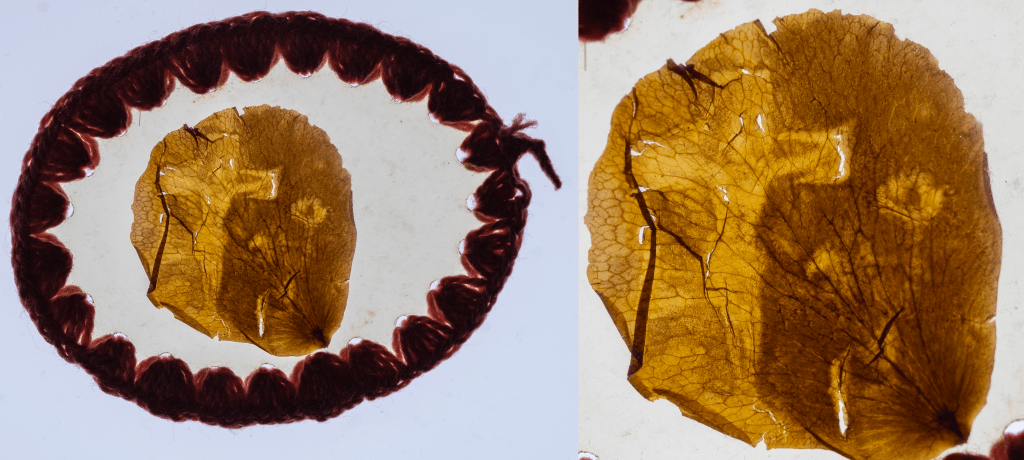

Inspired by my grandmother’s allegedly miraculous rose petal, I spent two years devising methods of manufacturing my own rose petal images to understand how this alleged acheiropoieta might have been conventionally produced. Scratching and pressing the petals with metal tools and plates proved to be ineffective, as the fragility of the plant matter made the task nearly impossible. I ultimately tried an alternative photographic chlorophyll process whereby the sun’s UV properties would bleach organic plant matter. These images initially have good clarity, but they reveal a very short shelf life as the petals continue to naturally decay and decolorize.

According to my family sources, my grandmother’s petal dates to at least the 1930s, and the permanence of its image is still clear as day. The image can also be seen almost identically from both sides, and no image I attempted preserved that level of quality or transparency. To the best of my knowledge, I cannot currently account for how that image would have been produced.

Viewers can engage with the rose petals on display in the exhibition by using magnifying glasses and a gold-gilded digital microscope, providing a technological, scientific apparatus for scrutinizing the alleged acheiropoieta. They are encouraged to wear white cotton gloves contained in a nearby bowl when handling the objects. This primes the subject into a few modes of associative thinking: Not only are white gloves associated with the handling of sensitive materials, especially in archives, but they also signify heraldry and are considered a sign of purity, cleanliness, and nobility in many professions. Notably, white gloves are also worn by and associated with stage magicians, a skillset designed to trick and deceive with permission from the audience. Artist and Research Trevor Paglen notes this in his discussion of AI and PSYOPs, quoting the magician James Randi:

“Magicians are the most honest people in the world.

They tell you they’re going to fool you, and then they do it.”

The priming of the subject is a quintessential action within an influence campaign, according to Paglen. Citing the 1988 US Army Field Manual’s principles of military deception, Paglen writes that it is easier “to induce the deception target to maintain a pre-existing belief than to deceive the deception target for the purpose of changing that belief.” By encouraging visitors to wear a set of gloves as they enter the exhibition and showing them a statement that provokes questions about what they are seeing, participants are primed to be skeptical and aware of manipulations taking place.

More importantly, the symbolic gesture of wearing gloves literally provokes a change in the viewer’s cognition, a phenomenon that researchers Hajo Adam and Adam Galinsky term “enclothed cognition.” In a study gauging the level of attentiveness to a task, users who wore a lab coat performed with greater attention than those not wearing a lab coat, suggesting that the embodying of a symbolic role, even subconsciously, can influence a user’s actions.

As a person of faith, I want to believe that my grandmother’s rose petal is truly miraculous. I want to believe that AI-generated images can be used for ethical and productive purposes. I want to believe that empirical, universal truths exist and that we can arrive at them through both faith and reason. It is my hope that with careful discernment, media literacy, and a willingness to engage with the archive of information, one can re-assert sovereignty in our treacherous landscape. I completed this project with a deeper respect for mystery and a greater faith. It challenged me to reflect on my religion’s relationship to truth through its visual traditions, and what the future of images, in general, might be.

Felt Presence | The Roses | The Images | The Relics | The Pilgrimage | Response to Benjamin