Felt Presence | The Roses | The Images | The Relics | The Pilgrimage | Response to Benjamin

Saint Therese of Lisieux lived from 1873-1897 and died at the age of 24 from tuberculosis. In her life, she dreamed of becoming a great saint, and she swore on her deathbed that she would return in a “shower of roses… spending her Heaven doing good upon the Earth.”[1] Because of her immense theological contributions to contemporary Catholicism, Pope John Paul II made her one of only four women “Doctors of the Faith.”

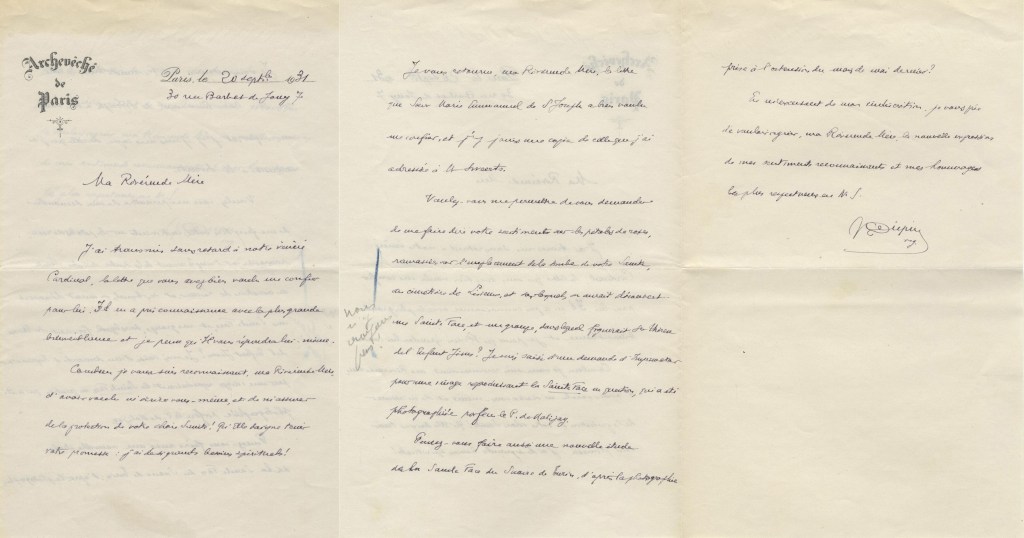

Some devotees of St. Therese believe that when her intercession is called upon, she manifests to them through the miraculous appearance of roses or petals. In the course of researching these anecdotes, I found a digital image that is popular among Therese’s devotees. The picture shows a French-language pamphlet, dating to the 1930s, which alleges that during Therese’s 1923 exhumation when her body was moved to the chapel of the monastery she had lived in, a rose petal was discovered that bore the image of the face of Jesus. This rose petal was then photographed by Nogieur de Malijay, a prominent Shroud of Turin researcher who assisted with its first photographs, and illustrated by a painter named J. Sailly. These two reproductions, image and illustration, are included in the pamphlet as proof of its existence.

On internet forums, this digital image is usually accompanied by personal testimonies or images of roses, and belief in the legitimacy of the story varies widely. Some comment asking for St. Therese’s intercession in their lives and for loved ones, while others deny the story. This is a contemporary case with a beloved saint, and I took it upon myself to discover if there was any truth to the story. I wrote to the archivists at the Carmel de Lisieux to inquire about their holdings related to this case and was delighted to find that they did have more information.

Listen to the text of the pamphlet:

According to the archive, Bishop Victor Dupin wrote to Mother Agnes of Jesus, the Prioress of the Carmelite monastery and Therese’s sister, on September 20th, 1931. Dupin explains that he was asked for an imprimatur by the writers of the pamphlet, a kind of “seal-of-approval” that would certify that it contained no doctrinal issues. However, within the margins of the letter is a post-script, written in pencil, which says, “We don’t believe it!” The archive explained to me that we don’t know if or what Mother Agnes replied, but it appears that Bishop Dupin signed the imprimatur anyway. Otherwise, any information on the whereabouts of the petal or images in question seems to be lost to time.

Listen to the text:

I couldn’t help but laugh at receiving this correspondence, as it seemed to typify everything I’ve come to expect from this study. I set out, in a good faith gesture, to solve what should be an easy-to-answer question, only to come up with more questions. Adding insult to injury is the pamphlet’s association with Shroud of Turin researcher Nogiuer de Malijay, whose photograph of the alleged miraculous rose petal and the Holy Face of Jesus emblazoned on it seem to haunt me with their claims of objective truth. Was I staring at the product of pareidolia, the human brain’s hard wiring to recognize patterns in random data, or the face of a Savior, a personal message written for countless faith seekers who had eyes to see?

The Pilgrimage

Though not official church doctrine, there is a widespread belief among Catholic laity that relics can be separated into first, second, and third-class categories. According to this popular practice, first-class relics are the literal body parts of the saint, such as their bones, blood, or flesh. Second-class relics are those items that a saint owned, wore, or interacted with to such a degree that they would be elevated in status. This would include items like a monk or nun’s habit, a beloved cross, or a frequented Bible. Finally, third-class relics are any item that has been touched to a first-class relic.

The Catholic Church’s official guidance on these treasured items was updated in 2017 and divides relics into two categories: significant and non-significant. Significant relics are the bodies, notable parts of the body, or the ashes resulting from the cremation of saints. Non-significant relics are smaller parts of the body and objects that have come into direct contact with a saint. All relics must be preserved and presented in sealed containers with a “proper certificate of the ecclesiastical authority who guarantees their authenticity,” and “honored with a religious spirit, avoiding every type of superstition and illicit trade.”

Both popular traditional practice and official church sanctions support the belief that the “felt presence” of a saint can transfer to an innocuous object by touching the item to a saint’s body part. If I were to find a first-class relic of Therese of Lisieux, I could “make” the story outlined in the pamphlet true. My study of manufactured rose petal images showed me that it would be possible to place a representation of the Holy Face on a petal, and if I were to touch this petal to Therese’s relics, I could confirm the essential details of the story. The Catholic Church’s official stance on insignificant relics affords this opportunity to exist.

This would not be a trite dissection of the relic system or a tongue-in-cheek response to the morass of the archive. The deeper my research went into miraculous images and the life of Therese of Lisieux, I became completely enamored with her story and her personal philosophy called “The Little Way.” To conduct this action would be a culmination of my research study, and it would also be a pilgrimage. I genuinely hoped that my heart and intellect would be moved and that I would encounter the “felt presence” of Therese of Lisieux. To engage with her presence and to make a third-class relic would help to fulfill her mission of spreading her emanation – her desire that she “travel over the whole Earth.” 1

Swipe or click right. AI-augmented photo of Therese’s 1923 exhumation, presented alongside an unedited photo from the same event.

Origins of Relics

As I was reconciling what it would mean to work with AI images within this installation, a concurrent theme began to develop. Because AI-generated images are the product of their training set, often revealing ghostly clues and “hallucinations” that reveal their sources, I began to reflect on the idea that art can “capture” the soul, essence, or aura, of its author or its subject, or in some cases, can assert an “aura” in and of itself. In what ways are images like relics?

Within the Catholic tradition, relics find their origins in the early martyrs, those people who died for their convictions in their faith. Even though the now-deceased person was believed to exist in Heaven, their mortal remains left behind on Earth were believed to still hold a living “praesentia,” or “felt presence,” that devotees could call upon, interact with, and venerate.[2] Veneration, the act of giving reverence and honor to a person, place, or thing, is an important distinction from worship, which is intended for God alone. It is for this reason that the intercession of the saint could be called upon. The saints themselves do not have the power to heal or offer blessings, but because of their virtuosity and holiness, are believed to be closer to God and therefore more capable of acting on behalf of their devotees to God. To believers, calling on a saint’s intercession is not unlike asking them to “put in a good word with the boss.”

Informed by the theology that Christ’s presence was inherent in each division of the Eucharist, or sacramental bread, devotees of the cult of the saints believed that each fragment of a saint’s body, and even their personal belongings, could contain their presence. These items, now termed relics, were distributed among the early churches and protected by their devotees, creating incredibly influential cults that surrounded these individuals.

On the modern relevance of relics:

Quoted in Guy Gaucher,

“Christianity isn’t made up of abstract ideas and isn’t a philosophical system. It’s a religion of flesh and blood. There’s no Resurrection without death and no salvation without an Incarnation.”

I Would Like To Travel the World: Therese of Lisieux, Miracle-Worker, Doctor, and Missionary, 119.

Many traditional practices arose in early Christianity to venerate these relics, including pilgrimage to a shrine or burial site of a saint, housing the relics in highly decorated art objects called reliquaries, and the creation of images of the saints to display alongside their relics.[3]

Reliquaries can dramatically range in appearance, from literal “houses” and tiny chapels meant to mimic a casket, shrine, or grave site, to recreations of body parts meant to identify the aspect of the body that the relic reflects.[4] Outside of established historical practices, reliquary can also arise out of practical needs and folk expression, as is the case with my grandmother’s rose petal reliquary, a simple semi-flexible plastic housing bound in red thread to prevent rough handling of the delicate object. An internet search of rose petal reliquaries displays massive amounts of variability arising from folk practice, including laminating the items, housing them in ornamental lockets, and preservation behind glass.

Images of the saints displayed alongside their relics served multiple purposes, including providing narrative context to their lives and educating an illiterate population through visual means. Most notably, as the tradition developed, the images themselves were believed to contain the presence of the saint regardless of display alongside relics, a tradition that is seen most prominently in Orthodox Christianity’s veneration of images. However, this practice prompted concern that the image would become the locus of worship, as opposed to the saint or God themselves, prompting the rise of the Byzantine iconoclast movement and the destruction of such images.[5]

The development of photography made possible new ways of perceiving this iconographic tradition, and nowhere is this more prevalent than in photographer Shannon Taggart’s elucidation of the Spiritualist religion in her body of work titled Séance. I was fortunate to meet and speak with Shannon at an exhibit of her work at University of Maryland, Baltimore County, where she highlighted the fact that Catholicism is to iconographic paintings as Spiritualism is to iconographic photographs.

Spiritualism is a religious movement originating in upstate New York in the 1840s whose popularity was buoyed by the simultaneous development of technologies such as the telegraph and photography, which were believed to be capable of bridging the gulf between the living and dead. Spiritualists practice that consciousness persists after death and that these “spirits” can continue to interact in the living world.

Photography became an important iconographic medium to the Spiritualists. The idiosyncrasies of photography, namely lens flares, blurring due to long exposure times, and double exposure gave rise to the hoaxing tradition of “spirit photographs,” which alleged to capture the visage of deceased loved ones. But even outside of this hoaxing tradition, for the first time, family members were capable of owning images of their loved ones, reproducing their likenesses without any artistic flourishes and which would persist after their death. These photographs became heirloom items and relics in their own right, believed to house the presence of the living or dead, as the reflected light that is recorded and fixed on the image has literally touched the individual (Barush: 40:28-41:02).

Photography’s relationship to magic, hoaxing, and trickery as a means of inspiring belief cannot go unmentioned when addressing the question of AI-generated images. Chesher and Albarran-Torres note that the black-box nature of AI image technologies produces an effect whereby the instantaneous production of an image from text suggests a magical invocation, working with a non-human intelligence as one might channel in a séance or through a Ouija board. This is confirmed by the self-reporting of users who describe the technology as spooky, eerie, uncanny, and awe-inspiring.[6]

In this case, the AI-generated image is less the container of an “aura” or “felt presence,” but the technology itself acts as a vessel or mediator to a non-human intelligence. This conclusion, that engagement with technology is akin to a religious experience with an “other,” has been studied extensively, especially as it is applied to belief in Marian Apparitions and photography as relic.

Technology as Mediator for the Divine

Anthropologist Daniel Wojcik conducted an ethnographic study[7] of the use of “miraculous polaroids” at the alleged Bayside, New York Marian Apparitions site, which took place between 1968 and the 1990s. During one of these events, Veronica Lueken, the visionary, stated that the Virgin Mary commissioned those in attendance to take photographs, which would be imbued with symbolism and an undeniable “special presence” that devotees could use as proof of miraculous occurrence. The preferred photographic method at such sites is Polaroid photography which develops on the spot, confirming, for those who believe, that no production or post-production processes were used on the image. This creates a certainty in the photographer that any out-of-the-ordinary results seemingly come from an unseen source, and are therefore a means of communication with the Divine, or that the images themselves result from the Divine. In this way, Wojcik compares this tradition of “miraculous photography” at sacred sites to the tradition of acheiropoieta. They are also not unlike relics in that they can travel and be shared and, in the case of photography, reproduced to spread their spiritual power.

The tradition of miraculous rose petals serves the same function. Whether created as a souvenir relic at a shrine, or acheiropoieta themselves, as is alleged of the contentious 1948 Lipa, Philippines Marian apparition site, rose petals housed in folk reliquary can travel the world, attesting to the presence of and offering access to the Divine and elevated status to their owners.[8] These practices are examples of how folk religion is experienced from the laity up, conflicting with top-down institutional religion when seeking popular acceptance.

Religious scholar Paolo Apolito highlights that one does not need to be a mystical visionary or sometimes even have faith to take a “miraculous photograph.” One needs merely press the shutter to render an image and for its hidden messages to be decoded by believers, expressing its esoteric meaning. Historically, the church would declare the meaning of an event or an image, mediated by the visionary in communication with several church-approved mentors. Now, our technologies, including cameras and the internet, have filled the role of the church and perhaps, have even replaced Mary herself. As Apolito puts it, “Protagonists are not as much focused on the idea of being chosen by the Madonna, as much as they are on the power of the instrument with which they are able to see what the naked eye misses.”[9]

My work is inextricably bound up in these themes because Felt Presence now exists within the material culture of the Catholic sacred. The photographs of the miraculous events of the Miracle of the Sun, photographs of Fatima’s child visionaries, and the collection of miraculous rose petals presented with very little context are all expressions of a “felt presence” of the Divine. They present themselves as relics in that they have been touched by and express unseen forces in their creation: the light emitted by the Miraculous Sun is recorded on a glass plate negative and the light reflected off of the child visionaries is likewise captured. And yet, their presentation invites folkloric narratives to extend beyond what is alleged in the gallery space. Any digitization of these images, presented on the internet as authentic, has the potential to proliferate new beliefs despite my intentions to the contrary. In releasing these images to the public, I ultimately have no control over how they will later be contextualized, and this is the dilemma we will forever find ourselves within in our post-modern technological landscape.

Relics as Sacred Object and Art Object

Perhaps the most notable aspect of a relic is that its “felt presence” is taken to be an inherent quality; it presents itself as a record. This fleshy object housed in a reliquary is St. Anthony’s tongue. This photograph is me on my 1st birthday. But these are stories we tell, some of which are so old and so beloved that they have superseded any expectations of truth and fall outside the realm of scrutiny. They become mythology, that which is somehow forever true, or as Joseph Cambell would state, “That which is beyond even the concept of reality.” How else do we make sense of the fact that there are four claims to the head of John the Baptist, claims which have existed for centuries and whose provenance is lost to time?

Belief in relics hinges on faith because often, there is no chain of custody or documentation to confirm the legitimacy of a relic’s provenance. These items were prized, and it is the adornment that certifies the truth of the physical matter. They must be taken together, for “unprotected, the relic becomes indistinct matter; emptied, the reliquary became a work of human art to be appreciated on its own or repurposed as material of some monetary value.”[10]

This is an unfortunate reality for both the relic and reliquary, wherein these sacred objects displayed in non-religious contexts may be reduced to an art object, which is a challenge faced by museums and art curators. Do curators work to contextualize the object as something sacred, by exhibiting it in a specific way and offering it its own space, or something secular, isolating it against the white wall of the gallery space?[11] In fact, much of the secular public perceives the museum as modern-day temples and their art holdings as modern-day relics.[12]

Museums are increasingly working to balance perceived responsibility to the religious public, providing them access to worship or venerate items that are understood religiously, while also seeking to educate the secular public on these objects within their original contexts and separately as artworks.[13] My exhibition toes the line, highlighting the curator as an authority figure in the same way that artists, scientists, and priests are. Sacred items are given context and dignity, but also neutral objectivity. In holding these tensions, the viewer can then bring their own experiences and discernment to the exhibition.

Continue the journey to find relics of St. Therese of Lisieux.

Felt Presence | The Roses | The Images | The Relics | The Pilgrimage | Response to Benjamin

[1] Therese of Lisieux. The Story of a Soul: The Autobiography of St Therese of Lisieux, page 203. Accessed online: https://archive.org/details/isbn_9781684221455/

- Quoted in Gaucher, I Would Like To Travel the World: Therese of Lisieux, Miracle-Worker, Doctor, and Missionary, 7. ↩︎

[2] Brown, The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity, page 50.

[3] Kreuger, “The Religion of Relics in Late Antiquity and Byzantium,” page 8. In Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics, and Devotion in Medieval Europe. Edited by Martina Bagnoli, Holger A. Klein, C. Griffith Mann and James Robinson. Yale University Press, 2010.

[4] Angenendt, “Relics and their Veneration,” page 25. In Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics, and Devotion in Medieval Europe. Edited by Martina Bagnoli, Holger A. Klein, C. Griffith Mann and James Robinson. Yale University Press, 2010.

[5] Kreuger, “The Religion of Relics in Late Antiquity and Byzantium,” pages 10-12. In Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics, and Devotion in Medieval Europe. Edited by Martina Bagnoli, Holger A. Klein, C. Griffith Mann and James Robinson. Yale University Press, 2010.

[6] Chesher and Albaran-Torres, “The Emergence of Autolography: the ‘Magical’ Invocation of Images from Text through AI,” 3-4.

[7] Wojcik, Daniel. “Miraculous Photography: The Creation of Sacred Space through Visionary Technology.” In Expressions of Religion: Ethnography, Performance and the Senses. Edited by Eugenia Roussou, Clara Saraiva and Istvan Povedak. LIT Verlag, 2019.

[8] Zimdars-Swartz, Sandra L. “Lipa Comes to Necedah: Personal Experiences, Signs, and aConfluence of Imagery at an American Cold War Apparition,” pages 103-105. In Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 21, no. 2, (November 2017): 100-110.

[9] Apolito, Paolo. The Internet and the Madonna: Religious Visionary Experience on the Web. The University of Chicago Press, 2005. Pages 116-117.

[10] Quoted in Nagel, Alexander. “The Afterlife of the Reliquary,” pages 211-212. In Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics, and Devotion in Medieval Europe. Edited by Martina Bagnoli, Holger A. Klein, C. Griffith Mann and James Robinson. Yale University Press, 2010.

[11] Paine, Crispin. Religious Objects in Museums: Private Lives and Public Duties. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013. Page 107.

[12] Ibid, 72.

[13] Ibid, 60.