Felt Presence | The Roses | The Images | The Relics | The Pilgrimage | Response to Benjamin

Although I had visited sacred sites while on travel or on vacation, I could not think of examples where I had set aside time and focus to engage in a deliberate action that I would call “pilgrimage.” The stereotype of walking long distances on foot in a state of prayer and meditation seemed so dramatically different than driving in a car and listening to the band’s music you will soon see at a concert, although I had to admit that this felt like a modern-day equivalent. As it turns out, I was not wrong.

Kathryn Barush is a scholar of art history and religion who specializes in pilgrimage studies and its correspondence with the art world. Barush builds on the work of anthropologist husband and wife Victor and Edith Turner, who developed the theory of “communitas,” the experience of “unmediated communication – even communion” that one experiences when on pilgrimage. This ineffable quality links the pilgrim to all those people who have experienced the sacred at the pilgrimage site before and after them, and it “arises spontaneously in all kinds of groups, situations, and circumstances,” creating an immediate felt presence of comradeship and dissolution of separateness.[1]

Barush advances a theory of “communitas-through-culture,” where encounter with a “symbol-vehicle,” be it a physical object, visual representation, song, or space, acts as a site of community “in and of itself:”

“Through the act of viewing or touch, the beholder connects to those who have encountered the object, images, or song before and those who will do so in the future… a feeling of connection with a community that is perceived, but not physically present.”[2]

Another attribute of pilgrimage is the taking or creation of souvenirs, which not only memorialize the action and serve as proof of travel but, according to Barush’s theory, become a site of communitas itself, “an ‘imaginative link’” to the original site which takes on a new “transtemporal dimension” and which the viewer can engage with.[3] Catholic material culture is replete with iconic souvenirs of pilgrimage, ranging from miraculous medals said to be commissioned by Mary herself to bottles of plastic water from the grotto at Lourdes. The ubiquity of paper and cloth souvenirs has always stood out as primary in my mind. My childhood was filled with memories of Sunday leaflets strewn across the kitchen table and prayer card bookmarks signaling worn pages.

The creation of third-class relics is a common way of fulfilling this record of travel, whereby touching the souvenir to a first-class relic, the devotees capture the “felt presence” of the saint or shrine to bring home with them. Likewise, the practice of documenting one’s travel, whether through writing, photography, or videography, all serves as a record-keeping practice that mirrors this desire to relocate the experience. Communitas is therefore no longer an ineffable trait, but a tangible, physical object.

The secular implications of communitas-through-culture confirm my suspicions that a concert is a kind of pilgrimage. However, it’s less the collection of fans that one engages with as the community, but the song itself, whose essence radiates throughout time as spoken voice, radio transmission, and recorded binary code, evoking powerful emotions and conjuring presence despite numerous contexts.

Inspired by this methodology and the numerous case studies that Barush outlines in her book Imaging Pilgrimage, I meditated on how I may apply these theories to my installation. By creating the third-class relic rose petal, I would already be making my installation a kind of sacred site, housing the felt presence of Therese of Lisieux. But how might I enkindle communitas-through-culture? Could I enable my viewers to enact pilgrimage themselves?

I wrestled with this question during the summer I was preparing to make my pilgrimage travel, and I was simultaneously helping to organize my maternal grandparent’s house for sale. I was unsurprised to find drawers in their house filled with prayer cards that claimed to be third-class relics of popular contemporary saints like the Italian stigmatic Padre Pio.

Recalling this ephemera made me think back to that digital pamphlet that inspired my pilgrimage. What if I recreated these pamphlets to give out at the exhibition? What if I made each of those pamphlets into a third-class relic, so that those leaving the gallery space would take home the presence of Therese? Such a souvenir would complete my pilgrimage and begin the viewers. The entire goal of the show was to provoke the viewer into encountering a “felt presence.” Now, they would have the opportunity to not only encounter the saint but take some semblance of the sacred home with them. That is – if they believed my narrative.

Searching for Therese’s Relics

As it turns out, Therese’s relics are an extremely popular attraction for the faithful, and have fulfilled her mission of “travel over the whole Earth.”[4] Since 1994, her relics have been on continuous world tour from their home in France, having visited nearly 70 countries and even having been launched into space aboard a 2008 Discovery shuttle mission. It occurred to me that if I was strategic, I could place myself at one of these public tour stops and conduct the third-class ritual, an opportunity that these relic tour events appear to afford the public. However, it looked like there would not be a tour near my area any time soon.

I was surprised to find large amounts of Therese’s relics housed in the United States, mostly in the Midwest, including a Shrine and museum dedicated to Therese located in Darien, Illinois. But beyond access to just Therese’s relics, I discovered two notable relic shrines that house thousands of relics of the Saints, the Maria Stein Shrine of the Holy Relics in Maria Stein, Ohio, and St. Anthony’s Chapel in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, which claims to be the largest archive of relics of the saints outside of the Vatican, numbering over 5,000. St. Anthony’s doesn’t list the relics they have in their collection on their website, nor do they advertise that the creation of third-class relics is something they publicly offer. However, they were the closest option in proximity to me, so I figured it was worth a shot. Correspondence with them was never replied to.

I continued my search for other options. An hour south of Maria Stein, at the University of Dayton, Ohio, I found the U.S. Catholic Special Collections library, which houses an archive of relics of the saints. I was fascinated that a university library would contain such a collection, and knowing that they were a research institution, I anticipated this would be my most likely candidate to pursue the project.

Initial conversations were fruitful. I discovered that the library considered its role as one of preservation. The relics in their collection were most often donated from estate sales or gifted from donors who could no longer care for them. I was told that the first-class relics of Therese of Lisieux they had in their collection were donated by a Carmelite monastery that was dissolving. I expressed that I wanted to make a short-form documentary with the archive about their relic collection and their preservation role, alongside the creation of my third-class relics. My request was elevated to the library’s director who cited that they had concerns about how my installation would be contextualized. Most notably, being a Catholic institution, they expressed that the amount of labor to, “verify that we are within the parameters of both the University guidelines and the Canon Law of the Catholic Church,” for the creation of hundreds of third-class relic pamphlets was something that they could not accomplish on such a short deadline.

Before replying to ask for clarifying details, I looked at the scholarship of those who worked for the institution to better understand these concerns. My experience with third-class relics had been almost omnipresent and lacked uniformity. It is not uncommon to find third-class relics for sale through shrine souvenir gift shops despite Vatican prohibitions citing the contrary, reflecting differences of opinion and practice among the laity and the institution. More concerning, however, is the prevalence of first-class relics for sale on eBay, which, according to eBay’s terms and conditions and government regulations, is not allowed as they are considered “human body parts.” This does not seem to stop any of the people claiming to sell first-class relics who I surveyed as an ethnographic study of the practice. The vast majority stated that they were selling the reliquary and gifting the body parts as a means of circumventing the rules.

As it turns out, the library’s director Kayla Harris had written about the very complex nature of this problem. As a university that collects Catholic ephemera, they are beholden to specific Canon Law about the treatment of “sacred objects,” namely that they are to be “treated with reverence,” “not made over to secular or inappropriate use, even though they may belong to private persons,” and that those who “profane sacred objects” are to be “punished with a just penalty,” highlighting the value they place on these objects.[5] Because of the volume of the materials they acquire from donation, much of which they must assume has been blessed or used in sacramental ways, they have come up with procedures for how to formally process and remove objects from the collection.

Paper ephemera specifically is one of the most complex areas of “deaccessioning,” or removal from a collection, because of the informal use and omnipresence of these objects that have the potential to be classified as “sacred.” For objects within their collection that require deaccession, common policies include offering them as free souvenirs at library exhibits, repurposing and gifting them to other institutions, and only in the rarest of cases would one burn or bury a sacred object per Canon Law. Calahan and Harris note that:

“We assume the best of our visitors, so although there is a possibility that an item will be used for a profane purpose, we view that risk as minimal. Once the [object] has a new owner, we cannot predict the future of that item; however, we have suspicions that some of the [objects] given away… are then later donated back by our very well-intentioned and devoted patrons.”[6]

I was mortified reading through this scholarship, reflecting on how my request must have been received. The natural result of producing so many third-class relic pamphlets is that inevitably, some would end up in junk drawers like at my grandparent’s house, while others would end up in trash cans or worse, hardly a dignified handling of a sacred object. I attempted to play damage control in my correspondence, expressing that a review of Director Harris’s scholarship gave me a newfound appreciation for their concerns and that I would be very willing to explore alternatives. While my response was met with sincerity and a note that they were not in the habit of turning researchers away from access to the collection, a variety of factors were at play, including changes in administration and their desire to sanction the project with a priest.

The most obvious factor whose attention I was neglecting was that my exhibition would be taking part in the material culture of Catholicism. While my exhibition is intended for all audiences and has much to say about how our art and technology have arrived at this moment, I had only loosely been thinking about my obligations to perception by Catholic and broader Christian audiences. Very early on in this project, a colleague warned me about working in religious art, citing several famous case studies of well-intentioned artists being vilified. The iconoclasm should have been front of mind, considering my research. I knew enough about my religious tradition to contextualize this material within an artist talk, but I needed to have it reflected in the exhibition itself.

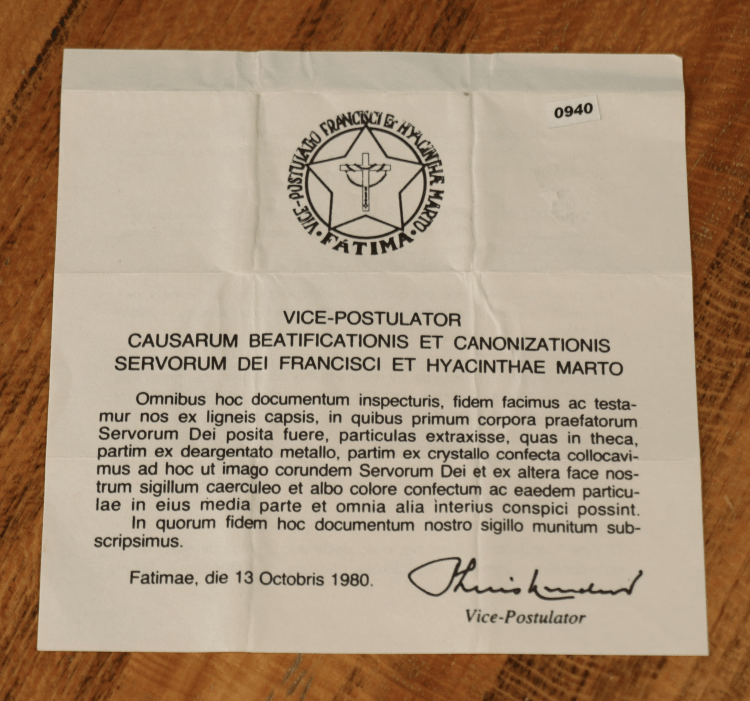

As luck would have it, the Maria Stein Shrine of the Holy Relics, just an hour north of Dayton, not only had first-class relics of Therese of Lisieux, but I was stunned to find that they also had relics of siblings Francisco and Jacinta Marto, the two youngest Fatima visionaries who died of the Spanish flu shortly after the Fatima events in 1919 and 1920 respectively. The two were made saints in 2017 and are recognized as the youngest saints in the Catholic church who did not die as martyrs. While my project did not call for third-class relics of their materials to be made, I already was in the process of creating glass plate negatives of the child visionaries so that gallery viewers would be able to put faces to the phenomena. In my pilgrimage to Maria Stein, I could elevate the negatives into a proper third-class relic. I decided it was time to reach out to see if they would be willing to work with me.

Swipe or click right.

Slide 1: The Fatima Visionaries: Lucia Dos Santos, and her cousins, Francisco and Jacinta Marto (L to R).

Slide 2: Jacinta’s exhumation, September 12, 1935. Wikimedia Commons.

Slide 3: Jacinta being carried away from the crowds after the October 13th, 1917 Miracle of the Sun apparition event.

The Maria Stein Shrine of the Holy Relics

In my initial conversation with Mark Travis, the director of the Maria Stein Shrine, I explained my intention to create a third-class relic of both a manufactured rose petal and of the actual letterpress plate used to produce the pamphlets given out at my exhibition. In doing so, the pieces of paper run through the press, making contact with the third-class relic, would not themselves fall into any specific category of the informal relic classification system. They would be relics, but merely “non-significant contact relics,” by the institutional Catholic definition.

I also expressed that I would be providing signage in the gallery space highlighting the Canon Law surrounding the Catholic Church’s current stance on relics. I would be displaying the relics in sealed containers and they would be “honored with a religious spirit, avoiding every type of superstition and illicit trade.”[7] All third-class relics would remain in my personal collection and no part of the exhibition was for sale, now or in the future. This was obvious to me, but felt important to state it to people not familiar with the project.

On that initial phone call, Mark explained that the Shrine is in the habit of honoring requests to make third-class relics, albeit privately. Most folks contact the Shrine looking for relics of specific saints whose intercession they seek for healings, with Saint Peregrine, the patron saint of cancer patients, being among the most popular. An entire wall is dedicated to those saints who are particularly popular with pilgrims, whether they be major names within church history like Thomas Aquinas or Francis of Assisi, or contemporaries like Mother Teresa of Calcutta and Maximilian Kolbe.

Mark explained that the Maria Stein Shrine perceived its role as one of patrimony within the Catholic church; they were the keepers of an ancient legacy they were fortunate to be endowed with. It is a great responsibility that weighs heavily upon them. As custodians of the relics, their job is to make them accessible to the public for intercession and inspiration.

The relics first came to Maria Stein by way of its founder, Father Francis de Sales Brunner who established the location as a cloistered convent in 1846. In 1872, Father J.M. Gartner was tasked with preserving and showcasing 175 relics in the New World for display to the faithful, and he intended a traveling exhibit to accommodate this. However, when he became aware of the relic collection at Maria Stein, he offered to combine the collections, which ultimately established the current shrine location in 1875.

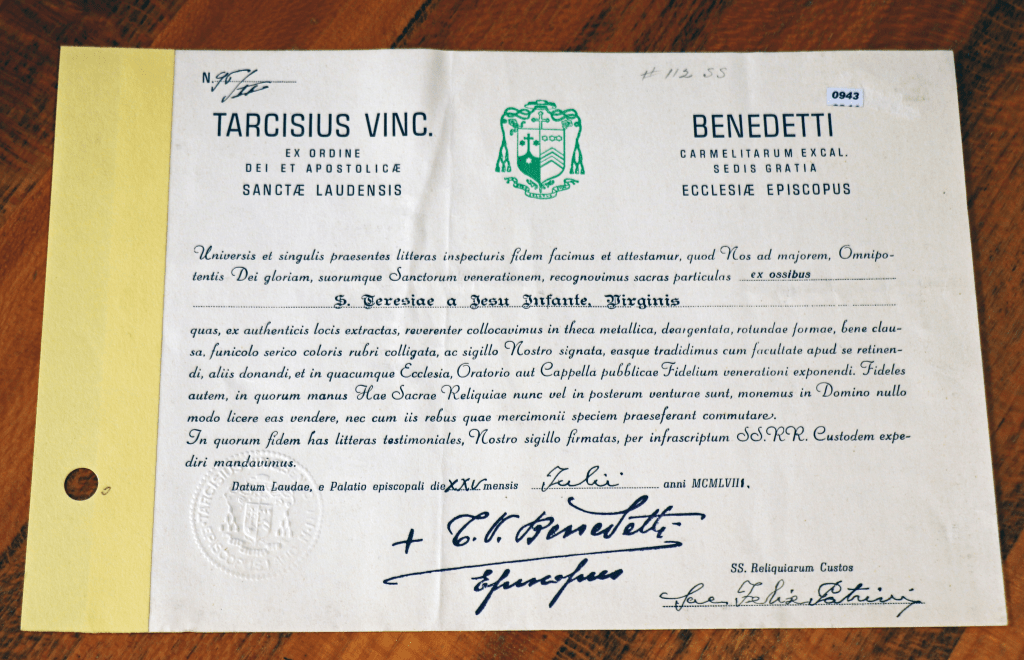

Mark explained that their contemporary acquisitions most often come from religious orders, the Vatican, or some other church-sponsored source and that they require provenance paperwork to bring an item into the collection. As part of their “custodial requirements,” each of the relics intended for public veneration must first be authenticated by a Bishop. The relic itself is tied with two pieces of red thread and then sealed with wax bearing the specific logo of the authorizing Bishop. A certificate outlining the provenance and dates of the relic is supplied with the relic itself, which must be signed by the same authorizing Bishop. I found this explanation fascinating as it justifies how the Church is responding to the critique of how a relic’s chain of custody is determined. In fact, a 2017 Vatican document outlines the modern procedure for creating relics, which can begin only after seeking permission from the heirs of the deceased, in accordance with local civil laws and state-of-the-science forensic and medical practices, and avoiding any publicity of the event.

It’s for these reasons that the contemporary saints I was seeking to encounter had extremely good provenance documents, which are displayed in my exhibition per Canon Law. Therese of Lisieux’s relic is a bone fragment, an authentic first-class relic, whereas Jacinta and Francisco Marto’s relics are pieces of their wood casket and therefore third-class relics, enclosed beneath images of the saints.

Swipe or click right.

Both Mark Travis and Director of Ministry Matt Hess were willing to admit that there is no way of confirming some of the oldest materials in their collection, which include items from the first century. While they lean on the value the Church historically placed on these artifacts as testimony for their authenticity, they explained that in the end, we have to have faith that the Holy Spirit guided these pieces through history and protected them down to today.

Upon arrival at the shrine in August of 2024, I was struck with the beauty of the space and had to admit that I felt the weight of “presence,” the communitas that both the Turners and Barush posit. Chalk it up to confirmation bias, but in being given a private audience at the Chapel before its public opening so that I could document the space and my process, I found myself emotional. I began by praying, asking for the permission and intercession of God and those saints present in the space that they may bless this project. I reflected on my graduate school journey, never anticipating the odd twists and turns that would bring me to this specific location. Finally, I prayed for my wife and child at home, who would be without me for the longest period since our child was born the year before.

Swipe or click right.

Mark Travis met me shortly after I began video documenting the chapel, and I was shocked to discover how young he was. In retrospect, I was imagining the community to be run by white-haired religious, bristling about in habits and robes. Wearing a polo tucked into tan khakis, he called to mind every high school athletics coach or youth religious education teacher I had interacted with, which, as it turns out, were his former jobs. Travis had grown up in the area and his mother was a devoted patron of the Shrine. After she received a terminal diagnosis, Travis came back to the area to help care for his mother. The job opened up and he took on the opportunity, looking forward to stewarding the space that had meant so much to them both. One of the relic cases hanging in the chapel is dedicated in honor of her memory.

We spoke briefly about my travel, and I explained to him how I had envisioned the pilgrimage to feel. It was difficult to feel fully present to the sacred because I was also here to work and had a limited amount of time. As I would discover later, my wife and child had come down with extremely high fevers, and I had to cut my plans short, racing the eight hours home through the night after a long day of working to help care for them. Travis explained that he envisioned the role of pilgrimage less as an act of “doing,” but more as an act of “being.” If we can humbly offer our presence and receive God in return, we will come out the other end of the pilgrimage transformed. Pilgrimage is intended to be a microcosm of the macrocosm, which is our journey towards God. I smiled and nodded in agreement, knowing full well that I would be lucky to have another moment to be “fully present” as I raced to accomplish all that I needed to.

His words stuck with me though, and throughout the day, lugging film equipment up and down staircases, I reminded myself to breathe and to say thank you to God for affording me this opportunity.

Travis began by procuring for me Therese’s first-class relics, the first of the collection that I would be documenting. Wearing white archival gloves to handle the delicate object, the reliquary accidentally opened as it was removed from its location behind a locked case. Travis took the opportunity to show me the wax thread and seal that I had only read about up until this moment. He explained that if the thread or seal were to be broken, the Shrine would be required to send them back to the Vatican or other church authority to be re-authenticated. Written entirely in Latin, the case appeared to make no mention of Therese’s name, although I could make out the name “Martin,” her original surname before entering the convent. Travis moved with such conviction that I didn’t question it.

Only later, as I began the process of arranging a table in a private room above the chapel, did Travis realize his mistake. Removing my rose petal reliquary and letterpress plate from the homemade boxes I had prepared for the occasion, Travis entered the room with another reliquary in his hands. Apologetically, he explained that the reliquary I was about to touch to my objects was actually the relics of Therese of Lisieux’s parents, Louis and Marie-Zelie Martin, who, in 2015, became the Catholic church’s first husband and wife to be canonized together. I was delighted and explained that, with Travis’s permission, I would like to continue the process of making these third-class relics with both reliquaries.

Despite obviously needing Therese’s relics for the conceptual underpinning of the exhibition, the objects would remain in my personal collection after the exhibition. To have Therese’s parents included in a personal shrine at home, an extremely rare instance of the Catholic Church exemplifying that married folk, even entire families, are capable of becoming saints, was something I had not expected to encounter. I reflected on how much my wife and newborn daughter had played muses to my work, and how they gave me the time, energy and support to make any of it possible. I viewed the Martin’s unseen presence in this project as a gift, one of Therese’s miraculous rose petals her devotees are so fond of testifying to.

Travis joked with me that in the process of creating the third-class relics, the gloves I was wearing would, by Church-definition, become third-class relics themselves. I knew instantly that they would become a fixture in the exhibition’s vitrines, and that I would wear them when producing the letterpress pamphlets as a continuous sign of the sanctity of the process.

I want to say that the process of making the relics was indescribably transcendent. But in reality, it was simple, formulaic, and grounding. It was not Therese, or the Martins, or the Martos who I meditated on, but my family at home, checking into an Urgent Care to discover the source of their escalating fevers. The distance between us was bridged by a connection of extremely deep love and longing. I reflected on Mark Travis, his family connection and love for this place, the stewardship he felt responsible for, and the opportunity he was affording me. The communitas I was experiencing was communion with every single pilgrim who, having traveled far from home, dreamed of reuniting with those they held dear. This is how I experienced the “felt presence” at Maria Stein, and beyond – a continuity of love that threads, binds, and entangles so that we are no longer just ourselves.

Read the conclusion of this study, a response to Walter Benjamin.

Felt Presence | The Roses | The Images | The Relics | The Pilgrimage | Response to Benjamin

[1] Turner, Victor and Edith, Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives, 250-251.

[2] Barush, Imaging Pilgrimage: Art as Embodied Experience, 6.

[3] Ibid, 7.

[4] Quoted in Gaucher, I Would Like To Travel the World: Therese of Lisieux, Miracle-Worker, Doctor, and Missionary, 7.

[5] Quoted in Calahan and Harris, “Mary, Undoer of Knots: Unraveling Best Practices for Unwanted Donations and Deaccessioned Collection Items in a Catholic Library,” 27.

[6] Ibid, 31.

[7] Vatican, “Instruction Relics in the Church: Authenticity and Preservation.”